The ‘Make in India’ initiative, launched in 2014, aimed to transform India into a global manufacturing hub by promoting domestic production and reducing reliance on imports.

This initiative got a major fillip with Apple announcing that the manufacturing of AirPods for export at Foxconn’s Hyderabad plant will start in April, according to PTI. This move signifies a major shift in Apple’s supply chain strategy as it diversifies its production locations beyond China.

The decision also underscores Apple’s growing importance in the Indian market, both as a manufacturing hub and a consumer base. This will potentially create new jobs and economic opportunities in the region.

‘Make in India’ aims to brand the country as a global competitor not only in sectors like automotive, textile, defence, and biotechnology but also in niche sectors like semiconductor manufacturing and the space industry.

Growing Imports from China

However, there’s a paradox. While the initiative aims to boost domestic manufacturing, rising imports and strategic partnerships with various countries suggest a reliance on foreign technology and investment. Recent trends suggest that despite these efforts, India’s import dependency, particularly from China, continues to grow.

As of February, India’s imports from China had likely surpassed last year’s record of $101.73 billion. According to data from the commerce ministry, the imports reached $84 billion in the nine months to December last.

The trade deficit more than doubled over the past decade, rising from $44.86 billion in 2015 to $101.28 billion in 2022, according to the Indian Embassy in China. This surge is driven by the import of critical components, such as electronic parts, pharmaceutical ingredients, and machinery, essential for India’s manufacturing sector.

In a recent report by Hindustan Times, a senior commerce ministry official justified the import growth, noting that most Chinese goods are raw materials or intermediary inputs. While officials argue that these imports support the ‘Make in India’ program, the widening trade deficit with China raises concerns about its effectiveness.

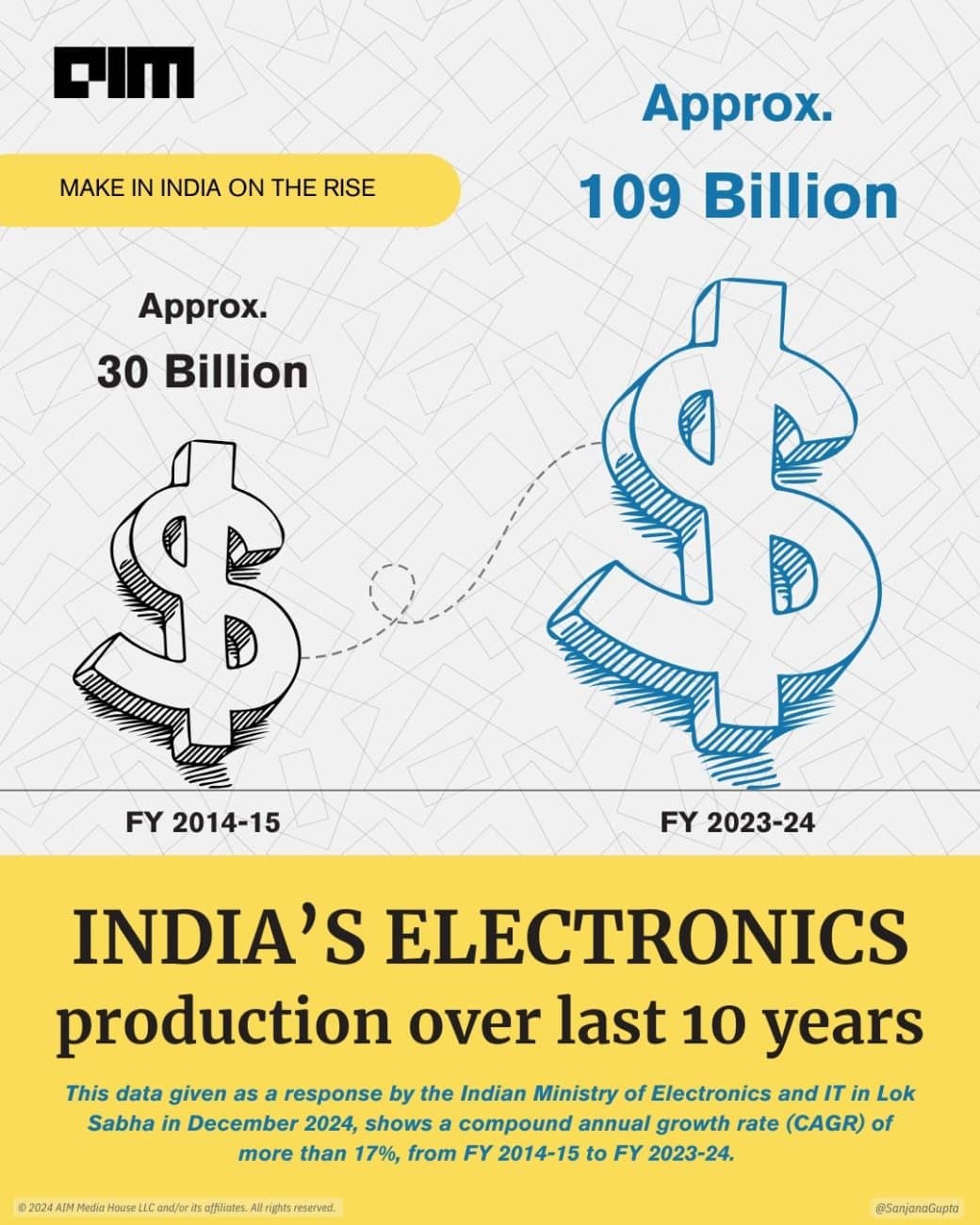

Regardless of the Chinese imports, India has made significant progress under this initiative. For instance, the production of electronics has grown from around $30 billion in FY 2014-15 to $109 billion in FY 2023-24 with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of more than 17%, as per the data given as a response by the Indian ministry of electronics and IT in Lok Sabha in December 2024.

Additionally, India’s electronic goods exports increased by 78.97 % from $2.29 billion in January 2024 to $4.11 billion in January 2025.

Another 2024 report from the commerce ministry indicates that India is now the second-largest mobile manufacturer in the world and has significantly reduced its reliance on smartphone imports, now manufacturing 99% domestically.

In a conversation with AIM, GV Joshi, an economist and former member of the Karnataka State Planning Board, mentioned that some level of imports is inevitable.

“The spirit of Make in India means [we should be] trying to produce as many articles as possible with the internal resources, without depending upon others for major, even elementary things,” he said.

He believes ‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’ needs to transcend a mere government initiative and become a deeply ingrained cultural philosophy. He points to the historically self-reliant districts in Karnataka as examples of the mindset required for true industrial independence.

Strategic Global Partnerships vs Domestic Production

In addition to the reliance on imports, India is also engaging in significant strategic partnerships.

In an interview with AIM, Manjunath Jyothinagara, MD at KASFAB Technologies, said that India’s push for aatmanirbharta (self-reliance) in semiconductor manufacturing has sparked considerable debate around ‘Make in India’.

When asked about the reality of manufacturing India’s first completely indigenous chip in Gujarat, he offered a practical perspective. Acknowledging that “the equipment is all coming from outside India,” he emphasised that the current efforts represent a crucial first step.

“It is made on Indian soil, using Indian talent and using some of the services coming from India. And that’s the first time.” He cautioned against unrealistic expectations, stating, “You cannot expect an ideal situation like we’d build tools and raw materials for that. Everything from India is not going to happen. I don’t think any country in the world functions like that.”

Instead, he advocates for an approach, defining ‘Make in India’ as “doing it here with a significant value add”.

Along similar lines, Jayashankar Narayanankutty, group director for sales at Cadence Design Systems, gave AIM his insights on India’s journey towards self-sufficiency in electronics manufacturing.

He highlighted the importance of the ‘Make in India’ initiative, emphasising that it is a gradual process. “Make in India is a journey where the value added to a product that is used in India grows over time. So, to expect that you go from a low percentage to 100% overnight is unreasonable,” he explained.

This perspective underscores the challenges of relying on imports, particularly for semiconductors, where India’s imports are substantial and comparable to oil imports.

Narayanankutty pointed out that while importing raw materials is necessary, the goal is to increase value addition within India over time. “This is why even in the government’s purchases today, multinational companies have to prove that a lot of what is happening is happening in India.”

Meanwhile, acknowledging the potential benefits of strategic global partnerships, Joshi cautioned that India must prioritise building a strong domestic foundation for its ‘Make in India’ initiative. He emphasised that the initiative is an ongoing journey that requires a gradual approach.

Joshi believes India needs to focus on strengthening domestic supply chains, fostering local innovation, and creating a supportive ecosystem for local manufacturing before fully embracing global collaborations.

Enhancing India’s Semicon Mission

When discussing the establishment of Kaynes SemiCon (a subsidiary of Kaynes Technology India Limited) OSAT project in Gujarat, Raghu Panicker, CEO at Kaynes SemiCon, highlighted the importance of aligning with the ‘Make in India’ initiative.

Panicker told AIM their technology partners are crucial in this endeavour, stating, “We intend to work with all the technology partners that will take care of the Make in India initiative.” He mentioned this while hinting at the upcoming partnerships with Japanese tech companies.

These partners are expected to contribute by providing a combination of technical support, raw materials, equipment, and other necessary resources. By leveraging partnerships with technology providers, they aim to ensure that the products manufactured in India meet the ‘Make in India’ criteria, which involves significant value addition within the country.

This strategy aligns with broader government initiatives, such as the India Semiconductor Mission (ISM), which offers incentives for domestic semiconductor production and design to reduce the reliance on imports and foster a robust semiconductor ecosystem in India.

Meanwhile, Narayanankutty expressed that the mindset of companies like Cadence needs to shift from a service-oriented approach to a product-oriented one. While considering that the change will be “difficult and time-consuming” for India, he stresses the need for this difference in mindset.

This was also iterated last year by India’s IT and electronics minister, Ashwini Vaishnaw. “India will become a product nation, and many products will come from deep tech sectors which will affect every citizen’s life,” he said.